Strategic Overview - Will MAGA Win the Midterms? - June 30, 2025

In this special Monday night strategic update, Tony Papert and Bruce Director step in for Kesha Rogers and Michael Steger

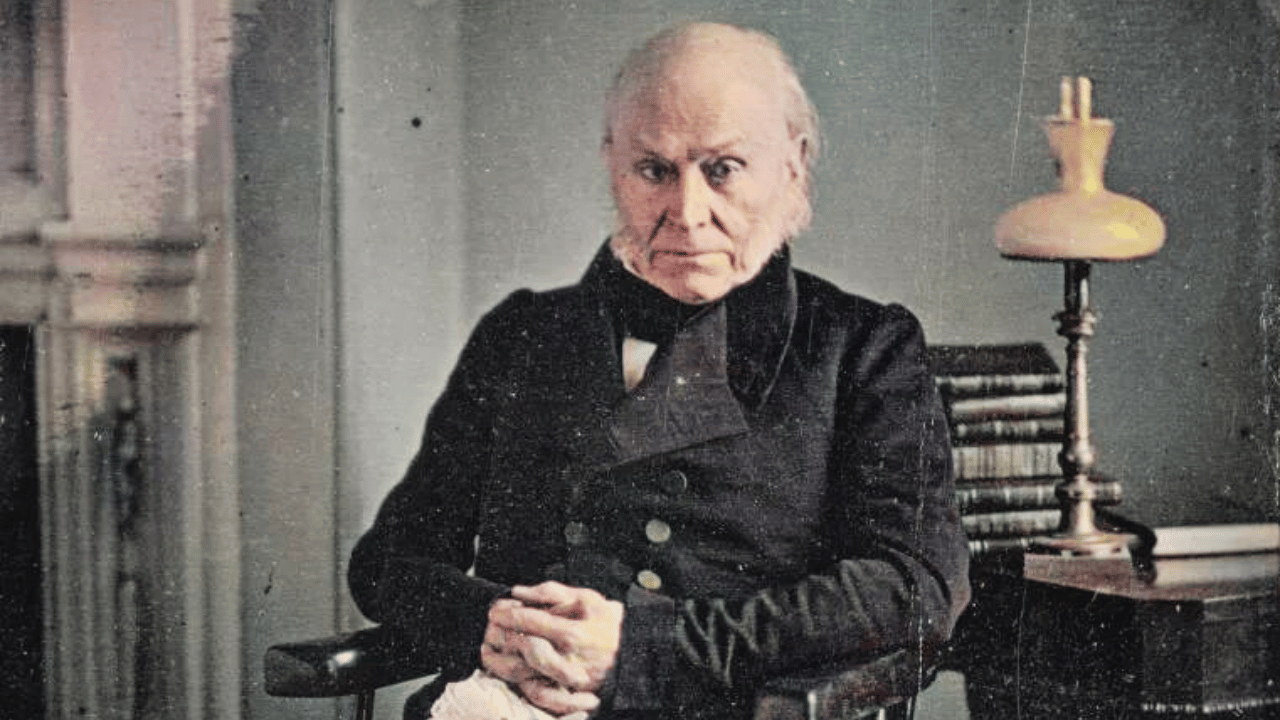

John Quincy Adams reflects on the birth of American independence, tracing the struggle from British rule to the Declaration's assertion that "all men are created equal."

July 4, 2024 marks the 248th anniversary of the issuance of the Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America, declaring themselves to be states free and independent of the oppressive hand of the British colonial overlords. For many years after July 4, 1776, and particularly after the predations of the British in the War of 1812, the anniversary was marked by gatherings in the town squares and town halls to hear the Declaration read afresh. It was on one such occasion, in 1821, on the 45th anniversary, that John Quincy Adams stood in a hall of the US Congress to deliver an address at the request of the Washington, DC Committee for Arrangements for Celebrating the Anniversary of Independence. It was a tour de force.

Then Secretary of State under President James Monroe, Quincy Adams delivered the address as a private citizen. Nonetheless, it caused some expressed discomfort among the largely European diplomatic corps who were among the attendees at the celebration. He prefaced his recitation of the Declaration with a history of the empire which, “from a small island in the Atlantic Ocean, had extended their dominion over considerable parts of every quarter of the globe.” Adams explains that, “governed themselves by a race of kings, whose title to sovereignty had originally been founded on conquest, spell-bound for a succession of ages, under that portentous system of despotism and of superstition which, in the name of the meek and humble Jesus, had been spread over the Christian world, the history of this nation had, for a period of 700 years, from the days of the conquest till our own, exhibited a conflict almost continued, between the oppressions of power and the claims of right. In the theories of the crown and mitre, man had no rights. Neither the body nor the soul of the individual was his own.”

“Through long ages of civil war, the people of Britain had extorted from their tyrants, not acknowledgements, but grants of right…. They received their freedom, as a donation from their sovereign.”

The subserviency to “ecclesiastical usurpation” and “holding rights as the donations of kinds” were not peculiar to the British people: “they were the delusions of all Europe.” Yet, “they could not forever extinguish the light of reason in the human mind.” The age of discovery, the creation of the printing press, the making of gunpowder, the improvement in the intercourse of man with his Creator—all this inexorably brought right and power into direct and deadly conflict. Not on the European continent, but in Britain alone was it undertaken, with only partial success, “so mingled up in every particle of the social existence of the nation” was conquest and servitude. It was in the heat of this war of moral elements, says Quincy Adams, “that our forefathers sought refuge from its fury, in the then wilderness of this Western World.”

Yes, they came with charters from their kings. But, “transported to a new world, they had relations with one another, and relations with the aboriginal inhabitants of the country to which they came; for which no royal charter could provide. The first settlers of the Plymouth colony…bound themselves together by a written covenant; and immediately after landing, purchased from the Indian natives the right of settlement upon the soil.

“Thus was a social compact formed upon the elementary principles of civil society, in which conquest and servitude had no part. The slough of brutal force was entirely cast off; all was voluntary; all was unbiased consent; all was the agreement of soul with soul.”

It did not take long for King and Parliament to exert their authority over the American colonies, so that, “long before the Declaration of Independence, the great mass of people in America and of the people of Britain had become total strangers to each other.” The colonies were treated “by the parent state with neglect, harshness and injustice.” Adams points out that in the 12 years that preceded the issuance of the Unanimous Declaration, the American people were as faithful to their duties as they were tenacious of their rights. “It was the deep and wounded sense of successive wrongs, upon which complaint had been only answered by aggravation, and petition repelled with contumely, which had driven them to their last stand upon the adamantine rock of human rights.”

It is at this point that Quincy Adams presented the Declaration, issued by the 13 United Colonies of North America, “exercising the first act of sovereignty by a right ever inherent in the people.” From that day forward, the American people were “no longer subjects leaning upon the shattered columns of royal promises, and invoking the faith of parchment to secure their rights. They were a nation, asserting as of right, and maintaining by war, its own existence. A nation was born in a day.”

Adams takes ironic note that, after 7 years of devastating, but heroic war, the most serene and most potent prince, George the Third, acknowledged, in the words of the 1783 Treaty of Peace, “the said United States…to be free, sovereign, and independent States; that he treats them as such, and for himself, his heirs and successors, relinquishes all claims to the government…and territorial rights of the same and every part thereof.”

Then came the hard part: “cement and prepare for perpetuity their common union and that of their posterity;…erect and organize civil municipal governments in their respective states; and…form connections of friendship and of commerce with foreign nations.” In the next 40 years, there were many modifications of internal government and the vicissitudes of peace and war, with other mighty nations. “But never; never for a moment have the great principles, consecrated by the Declaration of this day, been renounced or abandoned.”

In that time, Adams asks, what has America done for the benefit of mankind? “Let our answer be this—America, with the same voice which spoke herself into existence as a nation, proclaimed to mankind the inextinguishable rights of human nature, and the only lawful foundations of government.” In the assembly of nations, “she has uniformly spoken…the language of equal liberty, equal justice, and equal rights.” He notes that the contests of the European world will last for centuries. Yet, “wherever the standard of freedom and independence has been or shall be unfurled, there will her heart, her benedictions and her prayers be. But she goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own.”

A transcription of the Stone Engraving of the parchment Declaration of Independence (the document on display in the Rotunda at the National Archives Museum.)

In bringing his address to a conclusion, Adams asks again: what has America done for the benefit of mankind? It goes beyond invention, the inquiries into the mysteries of the universe. “Her glory is not dominion, but liberty. Her march is the march of mind.” So, “could that Spirit, which dictated the Declaration we have this day read, that Spirit, which ‘prefers before all temples the upright heart and pure,’ at this moment descend from his habitation in the skies, and within this hall, in language audible to mortal ears, address each one of us, here assembled, our beloved country, Britannia ruler of the waves, and every individual among the sceptred lords of mankind; his words would be,

'Go thou and do likewise!’.”

Get our free newsletter. Zero Spam.